Multiple factors make Afghan communities vulnerable to earthquakes

When

a magnitude-6.1 quake struck Afghanistan in June, long-standing

vulnerabilities — including a heavily faulted region, traditional

adobe-style construction, and lack of enforceable building codes — were

again revealed.

By Zakeria Shnizai, Ph.D., Kabul Polytechnic University and St. John’s College, Morteza Talebian, Ph.D., Research Institute for Earth Sciences – Geological Survey of Iran, Sotiris Valkanotis, Ph.D., Democritus University of Thrace, Greece, Richard Walker, Ph.D., University of Oxford

Citation: Shnizai,

Z., Talebian, M., Valkanotis, S., and Walker, R., 2022, Multiple

factors make Afghan communities vulnerable to earthquakes, Temblor,

http://doi.org/10.32858/temblor.266

A

magnitude-6.1 earthquake struck the Afghanistan–Pakistan border in the

early morning hours of June 22, 2022. Though relatively moderate in

size, the earthquake devastated Paktika and Khost Provinces in

southeastern Afghanistan, killing more than 1,050 people and injuring

almost 3,000 more. Three weeks later, on July 18, a magnitude-5.1

aftershock again rattled the region.

The

outsized destruction wrought by the quakes was promoted by geography,

regional economic fragility, and by the widespread use of traditional

adobe construction techniques.

A seismically active region

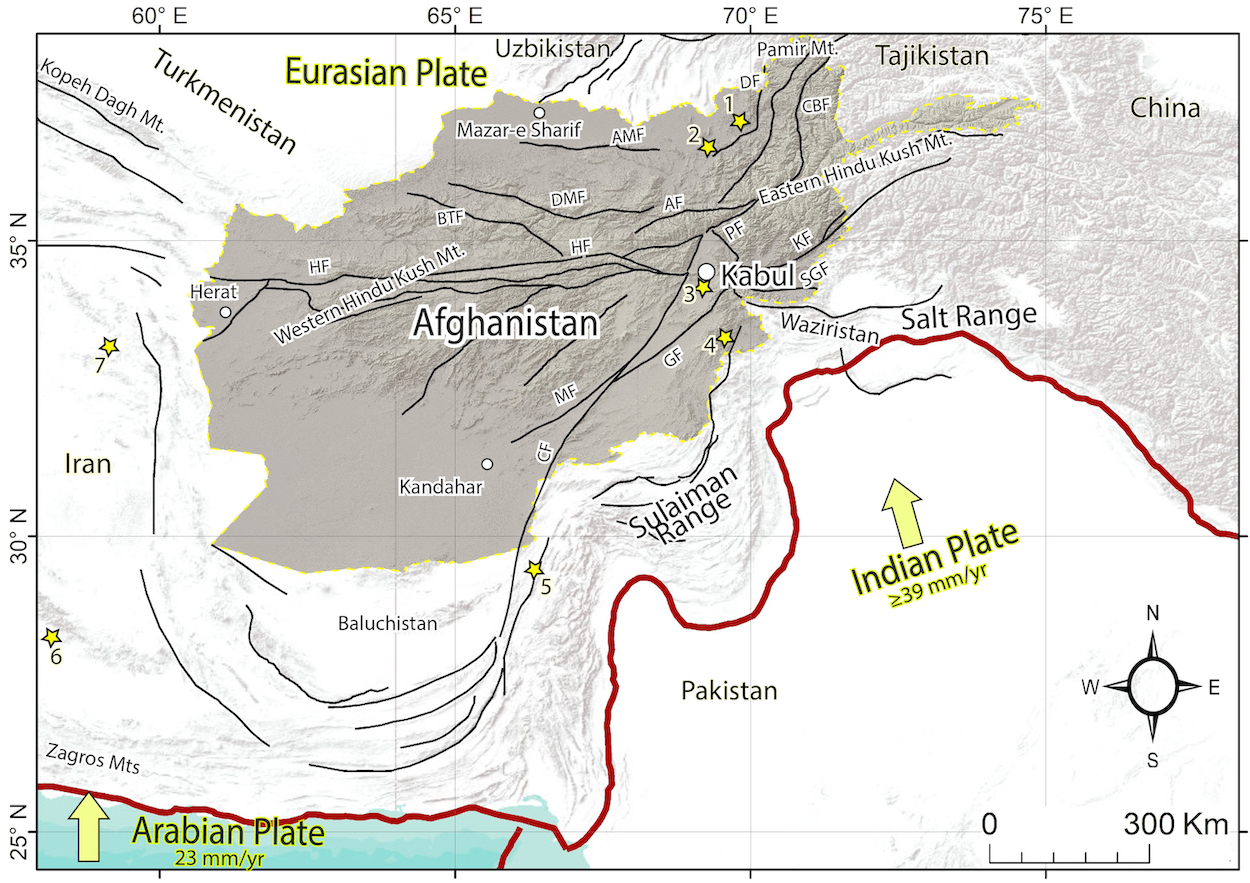

Afghanistan

is one of the most seismically active intercontinental regions in the

world. The country sits on the edge of the Eurasian tectonic plate.

Natural hazards abound due to the nearby slow-motion collision of India

into Asia. Northward motion of India at 1.5 inches per year (40

millimeters per year) dissects eastern Afghanistan and adjacent parts of

Pakistan with a series of northeast-oriented left-lateral strike slip

faults, in which rocks on either side of the fault move to the left

relative to the other side. Compression between the tectonic plates

results in shortening of the crust along thrust faults within the

lobe-shaped Sulaiman and Salt ranges.

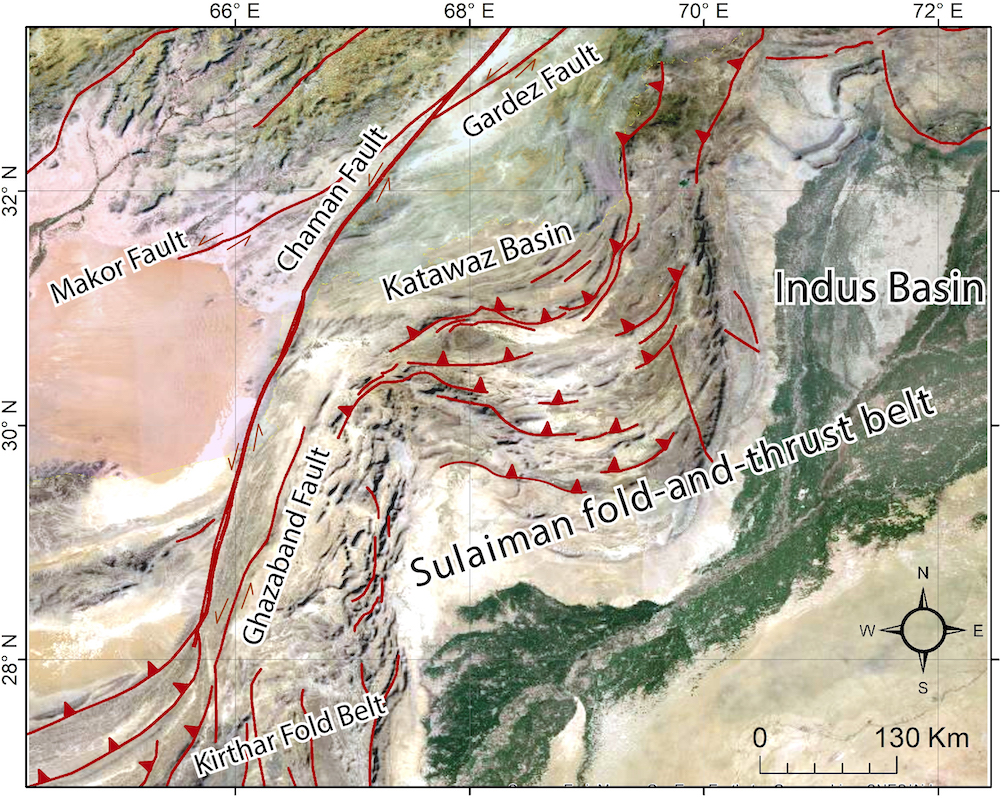

Simplified tectonic map of the Sulaiman fold-and-thrust belt on top of the ESRI basemap. Map compiled by Zakeria Shnizai

Active

faulting is distributed even more widely across Afghanistan; northern

parts of the country sit within the Afghan-Tajik depression — a large

low-elevation depression surrounded by high glacial peaks, floored by

sediments many kilometers thick, and cut through by numerous earthquake

faults — and the Herat Fault stretches across the country, almost to the

Iranian border. Within eastern Afghanistan, active faults raised the

great mountain ranges of the Hindukush and Pamir, as well as wide belts

of lower-elevation mountainous terrain, interwoven with low-relief

sedimentary basins bounded by faults.

Rural

populations are thinly spread across the mountainous regions. The

basins, with abundant arable land and fed by waters from the surrounding

high mountains, sustain higher densities of population, including large

urban centers such as Kabul.

Faults dissect eastern Afghanistan

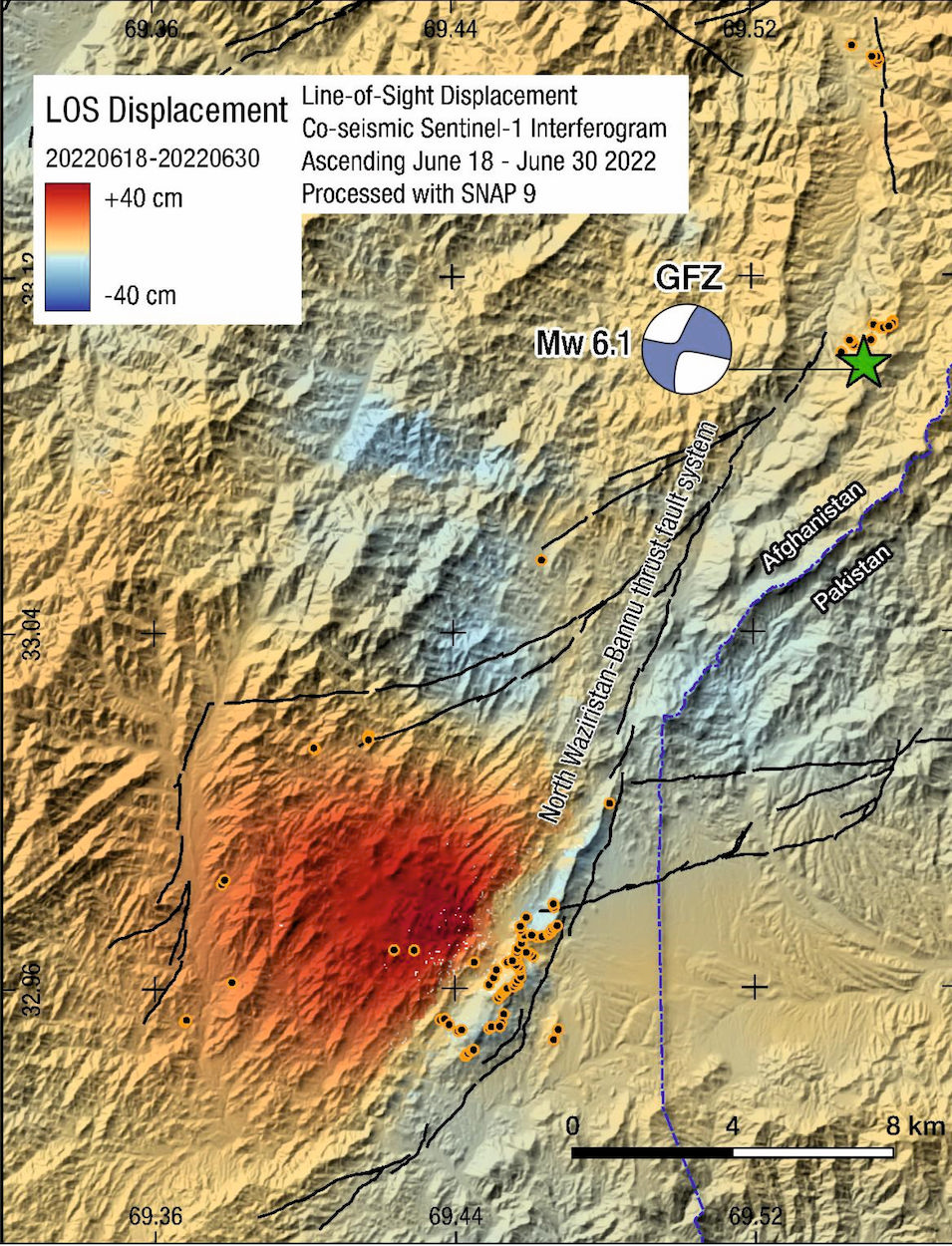

The

magnitude, location and focal mechanism for the June 2022 earthquake

have been computed from seismic networks around the world. Satellite

radar interferometry — a remote sensing technique that compares images

taken from a satellite over a period of time — has yielded detailed

measurements of ground displacement during the earthquake. Considering

these data, we determined that slip likely occurred on a roughly

north-south oriented left-lateral strike-slip fault parallel to, and

with an epicenter approximately 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) west of, and

into the hanging wall of, the North-Waziristan-Bannu Thrust Fault

system, in a region of exhumed and tightly folded sediments of Paleogene

and Quaternary age.

Focal

mechanism, epicenter, landslide distribution and line-of-sight (LOS)

displacements measured from InSAR. Shallow slip occurs along a

strike-slip fault ~2 km into the hanging-wall of the North

Waziristan-Bannu Thrust Fault, along the sharp eastern margin of the red

LOS displacements. Landslides (black and orange dots) are clustered

around the ruptured fault. Map compiled by S. Valkanotis using data from

the European Space Agency and showing focal mechanism and epicenter

from GFZ (German Research Centre for Geosciences, Potsdam)

The

quake resulted from the northward collision of India into Eurasia. The

most prominent structure within this zone is the Chaman Fault, which

extends for much of the distance from the Makran coast of Pakistan to

the Hindu Kush in northeastern Afghanistan. As the recent earthquake

highlights, the fault, though prominent, is only one part of a broad

zone of deformation, in which multiple widely distributed and often

unmapped faults are present that can rupture in earthquakes large enough

to cause significant damage and loss of life.

Regional

map of Afghanistan and the surrounding region. AMF, Alburz Marmul

Fault; AF, Andrab Fault; BTF, Bande Turkestan Fault; CBF, Central

Badakhshan Fault; CF, Chaman Fault; DMF, Dosi Mirzavalang Fault; GF,

Gardiz Fault; HF, Herat Fault; KF, Konar Fault; MF, Maqur Fault; PF,

Panjshir Fault; SGF, Spin Ghar Fault. The yellow stars with numbers show

locations of: 1) Takhar earthquake in 1998; 2) Nahrin earthquake in

2002; 3) Kabul earthquake in 1505; Paktika earthquake in June 2022; 5)

Quetta earthquake in 1935; 6) Bam earthquake in 2003; and 7) Tabas

earthquake in 1978. Map compiled by Zakeria Shnizai

Surprising damage, but a common occurrence

The

large death toll and widespread destruction caused by June’s

moderate-sized magnitude-6.1 earthquake are surprising compared to

others around the world; earthquakes of this magnitude and depth are

generally far less destructive. But in this region, the devastating

effects of earthquakes such as this are, sadly, all too common.

The

debris of a building after June 2022 earthquake in Paktika, Gayan

District Aston Galay Village. Photograph by Hamidullah Waizy, used with

permission.

The

June event is just one in a long line of damaging earthquakes that have

hit Afghanistan. More than 15,000 people have been killed in such

events in the last 24 years. Moderate to large earthquakes such as the

Takhar earthquake (magnitude 6.5) in 1998 and the Nahrin earthquake

(magnitude 6.1) in 2002 individually claimed the lives of thousands of

people.

Similar

situations exist across large parts of the interior of Asia, where the

collisions of India and Arabia with Eurasia have activated belts of

faults stretching from the Mediterranean to China, and where several

factors combine to increase the vulnerability of populations. Earthquake

disasters in Iran such as at Bam in 2003, Rudbar in 1990, Tabas in 1978

and Dasht-e-Bayaz in 1969, show the potential for devastation. The

Tabas earthquake, for example, a magnitude-7.3 quake, killed 85 percent

of the entire population in this rural region in the east of the

country.

Ruins

of a village near Tabas, depopulated in the 1978 earthquake (Mw 7.3).

Only a small number of homes have been rebuilt in the 25 years between

the earthquake and date of the photograph. Photograph by Richard Walker

What makes the population so vulnerable?

Obviously,

one of the factors that leads to increased vulnerability is the wide

distribution of active faults in the region. Although a few of the major

faults, such as the Chaman Fault in Afghanistan or the Main Kopeh Dagh

Fault in Turkmenistan, slip at rates on the order of 1 centimeter per

year (less than half an inch), other faults in the region slip more

slowly. The recurrence intervals between earthquakes in any one area may

be thousands of years. Because these shocks have not occurred in modern

history, they are rarely in the minds and cultural memories of local

populations and civic leaders. Without that memory, communities may not

be prepared for a major disaster and individuals may not know how to

protect themselves during shaking.

A photo from Kabul showing mudbrick homes built on steep mountain sides. Photograph by Zakeria Shnizai.

Construction

styles are a second major factor in the vulnerability of rural

populations. Unreinforced adobe construction with traditional building

methods is the dominant style of rural construction across much of the

Asian interior. Homes and other buildings consist of a thick flat or

domed roof of dried mud supported by timber, siting on walls of mud

brick or, in the case of the recently damaged villages in Afghanistan,

of stone blocks cemented with dried mud.

These

building styles are well suited to the climatic conditions. They

insulate from extreme heat and cold and make use of cheap and locally

sourced materials. They are, however, susceptible to collapse from

shaking, with the collapse of their heavy walls and roofs leading to

high fatality rates.

Building

damage from the 1997 Zirkuh earthquake, eastern Iran. The photograph

was taken five years later; note how structures (left) have been built

using similar materials and methods to the ruined pre-earthquake

structures (right). Photograph by Richard Walker

The

environment also plays a large role in vulnerability. Populations

across much of Asia are clustered in narrow fringes between desert and

mountains, which provide opportunities for settlement and agriculture

and offer pathways for migration and trade. But the mountain fringes are

formed by active faults. Springs along the faults are often the main

source of water, bringing life to otherwise inhospitable lands. Raised

groundwater levels at the mountain edges can also be tapped through

networks of Qanats — a type of underground canal. But the proximity to

active faults, when combined with the traditional building styles, make

nearby villages susceptible to even moderate, local earthquakes.

Reducing the risk

The

continuing occurrence of destructive earthquakes in Afghanistan and

surrounding regions provides an urgency in designing and implementing

strategies to reduce vulnerabilities to earthquake hazards. Large cities

and urban centers are expanding rapidly, with past settlements of

traditional adobe replaced by high-rise blocks. Kabul, for instance,

occupies a narrow north-south elongated basin that is bounded by faults.

It is an ancient city, with recorded large earthquakes in 1505 and

1891, yet its population and urban infrastructure has grown from 500,000

to 3 million over past decades. Quetta — farther south along the Chaman

Fault system in Pakistan — suffered a large magnitude-7.7 earthquake in

1935. Historical records also document damaging earthquakes elsewhere

in Afghanistan, including Herat, Mazar-e-Sharif and Kandahar.

There

is no quick and simple way to build resilience in regions such as those

damaged in the June earthquake, and effective efforts toward the

reduction of risk for future populations likely involve a wide range of

disciplines working together. Geological, geophysical and historical

analyses are all required to develop archives of past events, identify

active faults and ensure that urban expansion and infrastructure

development are based on the best available knowledge.

Engineering

has an important role through the design of simple strategies for

building with traditional materials and designs. But the success of any

program ultimately rests on the ability to convince populations that

there are ways of mitigating severe damage and loss by understanding

hazards and by improving construction methods, which in turn only fully

work if there are policy frameworks in place for their enforcement, with

financial support in place.

Over

the last few decades, Iranian scientists have worked to convince the

government of the increased risk from earthquakes as cities grow.

Collaboration between Iranian scientists and policymakers has now led to

development of building codes that are revised every five years to

improve building resilience. The latest update is expected to be

released in 2023 and will incorporate updated knowledge of earthquake

sources and active faults.

Within

cities, it is the responsibility of builders to follow such codes. In

rural areas, the situation is different, as building a resistant

structure requires legislation as well as financial support. In rural

parts of Iran, this support can come from long-term grants and loans

from the government, which are conditional on builders following design

standards and the guided plan of the village. Many villages with

vulnerable adobe buildings still exist; however, these efforts will

gradually improve the situation.

In

Afghanistan, earthquake-resistant construction design guidelines were

replaced with a formal building code in 2012. As in Iran, the building

of resistant structures requires not only a code, but also effective

enforcement and financial support. Much of the progress in Iran has

occurred immediately after recent earthquake disasters, before

governmental priorities shift to other concerns. We hope that if some

good can come from the recent Afghanistan earthquake it is in effecting a

long-term increase in resilience.

Acknowledgement

In

writing this article we are particularly indebted to the work and ideas

of Nicolas Ambraseys (1929-2012), Manuel Berberian, and James Jackson.

Further Reading

For

those wishing to learn more about the earthquake hazards of the Asian

interior, we recommend “A history of Persian Earthquakes” (Cambridge

University Press) and “Earthquakes in Afghanistan” (Seismological

Research Letters, 74, 2003) by Ambraseys and co-authors. We also

recommend works by Berberian and Yeats, including “Tehran: an earthquake

time bomb” (in GSA Special Paper 525), and the papers “Fatal

attraction: living with earthquakes, the growth of villages into

megacities, and earthquake vulnerability in the modern world” by James

Jackson (10.1098/rsta.2006.1805) and “Uncharted seismic risk” by Philip

England and James Jackson (10.1038/ngeo1168).